Strange TCP MSS values

TCP is today the most widely used transport protocol. It was defined in RFC793. It provides a connection-oriented bi-directional bytestream service on top of the unreliable IP layer. A TCP connection always starts with a three-way handshake. During this handshake, the client and the server can use TCP options to negotiate the utilisation of TCP extensions. These TCP options are also used to exchange a key parameter of a TCP connection: the Maximum Segment Size (MSS).

The MSS option is one of the few TCP options defined in RFC793. It is used by a host in the SYN packet that it sends to announce the largest TCP segment that it accepts from the peer over this connection. Upon reception of the MSS option, a TCP implementation stores it inside its connection state to ensure that it will never send segments that are larger than the MSS value advertised by the peer. Most hosts send MSS values that are slightly shorter than their MTU to prevent the fragmentation of TCP segments in multiple IP packets. RFC793 did not provide guidelines on how to set the MSS option. RFC879 suggested a default value of 536 bytes and IPv6 requires that all links have an MTU of at least 1280 bytes, which translates in an MSS of at least 1220 bytes.

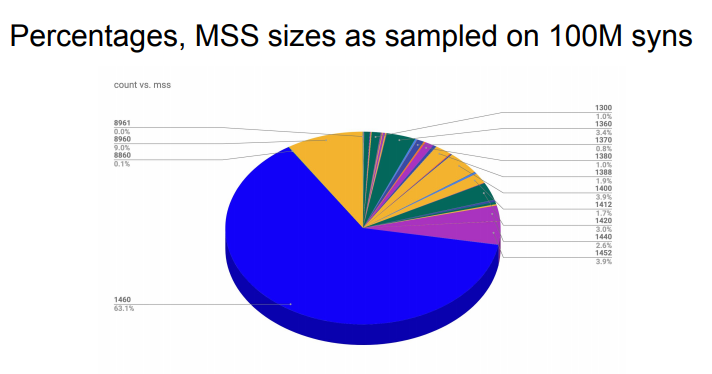

Most of the MSS values that are exchanged over the Internet are probably close to 1400 bytes, but a recent presentation by Joel Jaeggli at the July 2019 iepg.org meeting revealed some unexpected values. In June, several security problems were reported with the implementation of the Selective Acknowledgements in the Linux TCP stack (see CVE-2019-11477, CVE-2019-11478 and CVE-2019-11479). Using a very small MSS value made this security problem more severe and some system administrators used filters to block TCP connections where the client advertised a too low MSS value. Joel Jaeggli looked at 100 million TCP connections to collect the advertised MSS options. He found some very small values :

0 24 60 64 80 88 99 100 ...

and some very large ones

14760 15284 31749 47960 63910 63960 65420 65496

These unusual values are probably either linked to highly misconfigured or amateur stacks or some forms of security hacks or even attacks.

A summary of the collected values may be found in the chart below.

Geoff Huston also explored the same problem with another dataset in a detailed APNIC blog post.

This blog post was written to inform the readers of Computer Networking: Principles, Protocols and Practice about the evolution of the field. You can subscribe to the Atom feed for this blog. These notes are also posted on the ebook’s Facebook page