Experimenting with QUIC congestion control

Congestion control is one of the key functions of transport protocols such as TCP or QUIC. Students need to get both theoretical and practical understanding on how congestion control algorithms operate.

Experimenting with congestion control schemes can be difficult when these algorithms are implemented inside the operating systems kernel as with most TCP implementations. While from a pedagogical viewpoint it could be really useful to ask students to change some parameters of a congestion control scheme, asking them to recompile and install a new Linux kernel for each experiment would be a waste of time.

With QUIC, the situation changes since QUIC is entirely implemented as a regular library or application. There are several QUIC implementations in different programming languages. Since our students learned to program using python, we opted for aioquic a python implementation that supports many QUIC features.

During the summer, Anthony Doeraene, a student who recently finished his Bachelor degree in Computer Science at UCLouvain took the challenge of designing a set of lab experiments for congestion control using QUIC. He started with aioquic and included it in kathara. kathara is an open-source project that uses Linux containers running inside docker to emulate various network scenarios. A key advantage of kathara is that students can install it on their Windows, Linux or Mac computers.

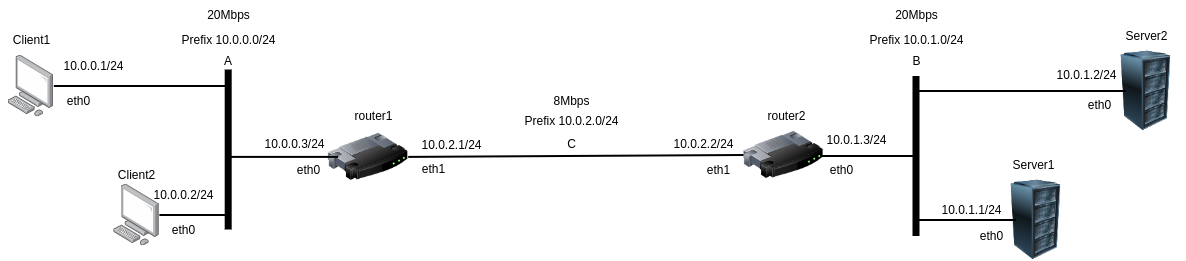

Anthony Doeraene started from a simple lab with two clients, two servers and a bottleneck link.

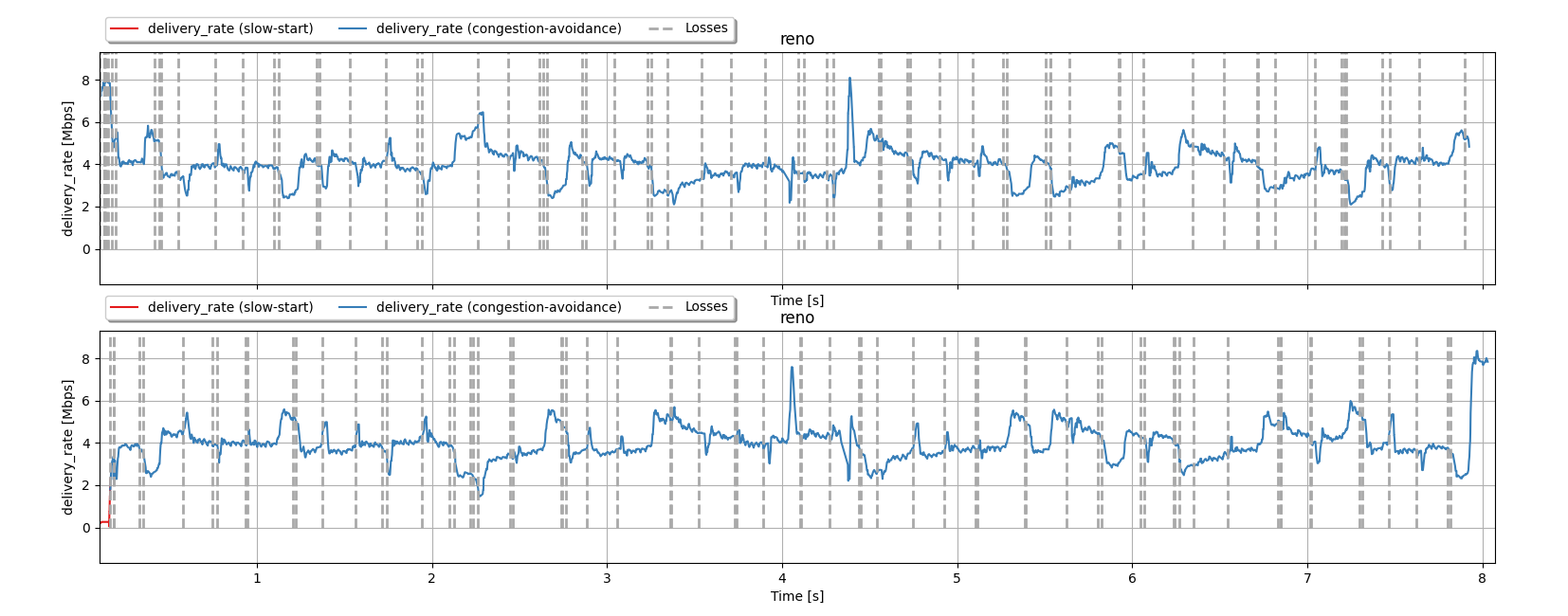

To demonstrate the importance of using congestion control schemes, he modified aioquic to disable the congestion controller and let the students explore the congestion collapse that occurs in this case if the senders use sending windows that are much larger than the router buffers. Then, the students explore the NewReno and Cubic congestion controllers. NewReno is the default congestion control scheme in aioquic but Anthony Doeraene added support for Cubic and also BBRv1 and BBRv2. With these congestion control schemes, the students explore the impact of the round-trip-time on the performance of the congestion control, the interactions between different congestion control schemes, … The lab ends with an exploration of FQ-Codel and its importance to ensure fairness with unresponsive flows. In addition to having enhanced aioquic and the scripts to automate a dozen of experiments, Anthony Doeraene also wrote nice python scripts to help students to visualize the results of their experiments. The figure below shows the evolution of two NewReno senders sharing a bottleneck link.

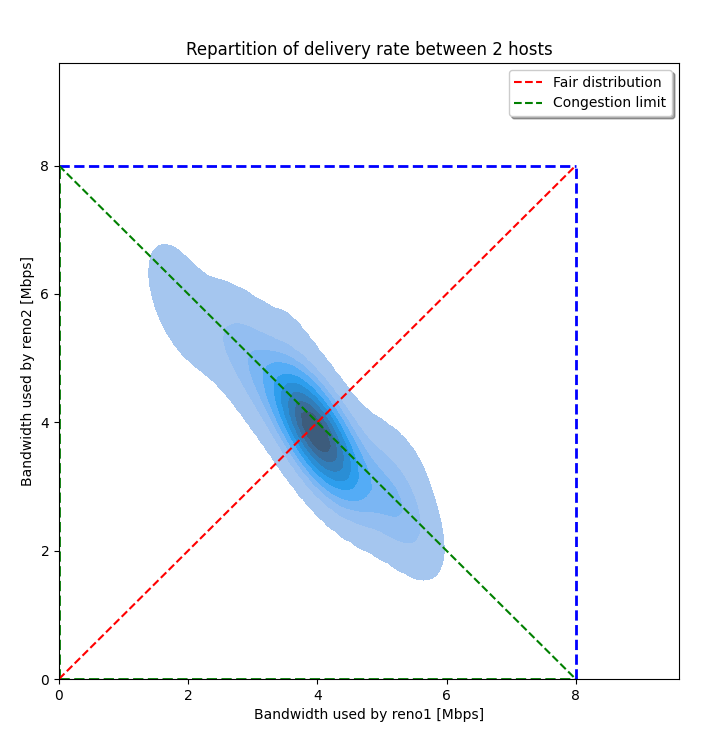

The figure below provides another viewpoint of the same experiment with a heat map of the throughputs of the two flows over time. It shows that NewReno was reasonably fair in this experiment.

These new labs will be used by UCLouvain’s students in April 2024. If you’d like to experiment with them before, feel free to contact Anthony Doeraene.

You can follow this blog by subscribing to its RSS feed or by following @cnp3_ebook on mastodon.