Using Class E IPv4 addresses, bad ideas will always resurrect

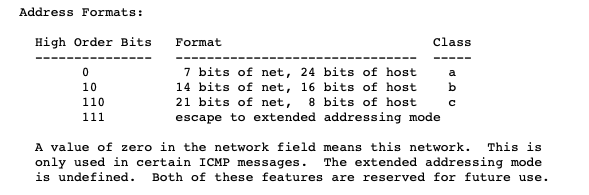

The IPv4 addressing space was initially designed as being divided in four classes of addresses. RFC791 clearly defined those classes of addresses as follows:

Later, RFC1112 updated this addressing space to further divide the fourth class in two parts:

Host groups are identified by class D IP addresses, i.e., those with “1110” as their high-order four bits. Class E IP addresses, i.e., those with “1111” as their high-order four bits, are reserved for future addressing modes.

Later, RFC1519 updated the addressing space to remove the division of the addresses in classes. Since then, IPv4 supports variable length subnets that have enabled it to continue to be deployed until using all available unicast IPv4 addresses have been allocated.

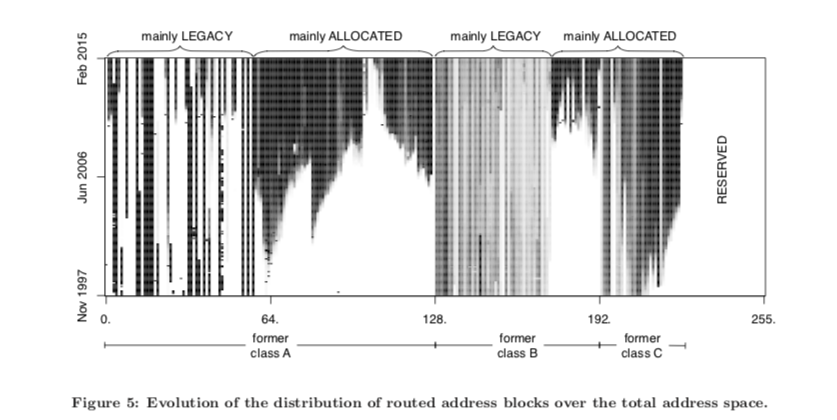

Various researchers have explored the real utilisation of the IPv4 addressing space. An interesting analysis appeared in A primer on IPv4 scarcity. In particular, the figure below extracted from this paper shows the evolution of the routable IPv4 space based on the BGP routes that are announced. It clearly shows that besides the large blocks of unannounced IPv4 addresses in the former class A addresses, most of the available IPv4 addresses are announced.

Given the scarcity of the IPv4 addresses, a market for IPv4 addresses has emerged. The companies that were allocated a large block of IPv4 addresses consider this as an asset and some have started to sell their IPv4 addresses like their Intellectual Property. For example, Microsoft agreed to pay 7.5 million US$ to buy the 666,624 IPv4 addresses allocated to Nortel when it went bankrupt. Today, the price for a block of IPv4 addresses is probably higher and some organisations continues to hold blocks of IPv4 addresses without fully using them. The United States Department of Defense owns 13 /8 blocks of IPv4 addresses, making them the larger user of IP addresses in the world.

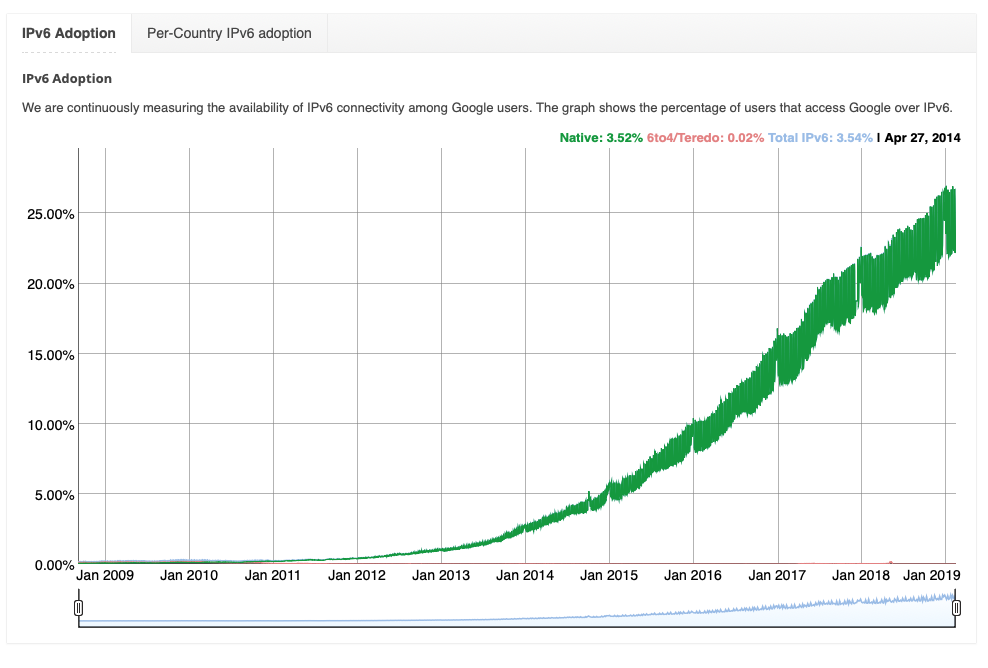

In the long term, investing in IPv4 is not the right approach. Everybody agrees that the long term solution is to continue to deploy IPv6. According to the statistics collected by Google, more than one fourth of its users use IPv6 in January 2019.

Unfortunately, some continue to believe in IPv4 and spent time in trying to extend the lifetime of this old technology. The last example is a forthcoming presentation at [Netdev 0x13]((https://www.netdevconf.org/0x13/) on Potnetial IPv4 Unicast Expansions. Their idea is very simple: reuse the Class E IPv4 addressing space to support regular unicast IPv4 packets. This idea has already been proposed several times in the past and never been finalised given the complexity of ensuring that a sufficient fraction of the Internet routers and hosts would be capable of forwarding those packets correctly. Unfortunately, they apparently managed to convince some router vendors and even the maintainers of the Linux kernel to accept their patches.

Instead of spending time and effort for therapeutic relentlessness on IPv4, deploy IPv6. You will obtain a stronger return on investment by migrating to an IPv6 only network than by continuing to rely on historic technology.

This blog post was written to inform the readers of Computer Networking : Principles, Protocols and Practice about the evolution of the field. You can subscribe to the Atom feed for this blog at https://obonaventure.github.io/cnp3blog/feed.xml.